Prometheus

Newsletter of the LFS

“Modern poetry” suggests to many people innovations in technique—free verse instead of sonnets, unconventional capitalization, and the like. If I thought such innovations actually resulted in writing better poems, perhaps I would agree but I don't and don't. To me, the interesting feature of modern poetry is content, not form.

Consider, for an example, “Hymn of Breaking Strain,” which takes as its central image the table of breaking strains in the back of an engineering handbook, a table which tells “what traffic wrecks macadam, what concrete should endure” but does not provide the same information for human beings who, like materials, are sometimes subject to strains “too merciless to bear.” That poem could not have been written very far into the past because no such tables existed then.

Or consider “The Secret of the Machines” and “The Miracles.” The subject of each poem is the miraculous world of modern technology:

You will find the Mauretania at the quay,

Till her captain turns the lever ‘neath his hand,

And the monstrous nine-decked city goes to sea.

…

I sent a message to my dear—

A thousand leagues and more to Her—

The dumb sea-levels thrilled to hear,

And Lost Atlantis bore to Her.

Behind my message hard I came,

And nigh had found a grave for me;

But that I launched of steel and flame

Did war against the wave for me.

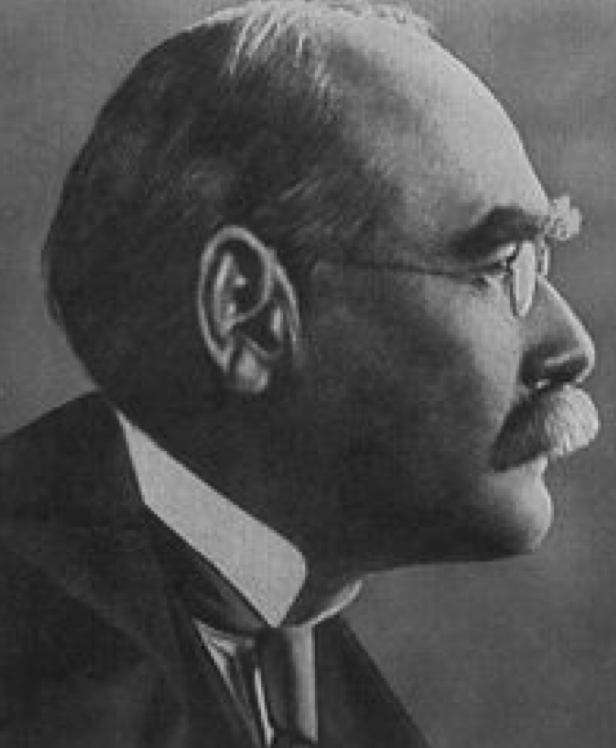

Which may help to explain why my favorite modern poet is Rudyard Kipling.

To be fair, , more conventionally thought of as modern for his stylistic quirks, has some modern content as well:

Lenses extend unwish through curving wherewhen

till unwish returns on its unself

Or the poem that uses driving a new car as a metaphor for making love to a virgin.

But Kipling is better.

Like most Kipling enthusiasts—he has been my favorite poet since I was about ten—there are a considerable number of his poems I am particularly fond of. My favorite is probably “The 'Mary Gloster,'” a Robert Browning Monologue, a poem in which a single speaker reveals a great deal about himself in the process of speaking, which I think is better than any of Browning's.

The speaker is a dying 19th century shipping magnate, a self-made wealthy entrepreneur, speaking to his worthless son. One of the impressive things about the poem is the degree to which the poet persuades us to the speaker's point of view. The son's interest in “books and pictures” ought to appeal to the modern reader—but doesn't. “[Y]our rooms at college was beastly more like a whore's than a man's” ought to turn the modern reader off—but doesn't. What the reader is left with is the picture of a bitterly unhappy old man whose only remaining wish is to be buried at sea by the wife who died when they were both young, the wife whose memory has been the driving force in his life ever since.

Another I reread recently is “Cleared”—a ferocious invective against the terrorism associated with the Irish independence movement. It is a bit of history that we almost always see with a pro-rebel slant, thanks to folk singers such as the Clancy Brothers and poets such as W. B. Yeats. It's interesting to see it from the other side.

Less black than we were painted?

Faith, no word of black was said

The lightest touch is human blood

and that, you know, runs red.

Kipling had a very high reputation, especially as a short story writer, early in his career, but fell out of critical favor later, I think mostly for bad reasons. Certainly he had politically unpopular views—but they were not the views generally attributed to him.

Perhaps the clearest example is the often quoted “For East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet,” taken to describe the fundamental gulf between European and Asian cultures.

Its point is actually the precise opposite, as one can see by reading the rest of the first verse, and still more clearly by reading the poem.

Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,

Till Earth and Sky stand presently at God's great Judgment Seat;

But there is neither East nor West, Border, nor Breed, nor Birth,

When two strong men stand face to face, though they come from the ends of the earth!

Similarly on race. Kim, Kipling's one entirely successful novel, is set in India. Most of the attractive characters are non-European. The Lama, after Kim the central figure, is a convincing portrayal of a saint—and Tibetan. While there are positively portrayed European characters, both the English and their European opponents mostly come across as incompetents dealing with a culture they do not understand very well, sometimes well meaning, sometimes not.

The book obviously regards British rule over India as a good thing, but not because of any innate superiority of the British. For further evidence of that, consider the two stories (“A Centurion of the Thirtieth” and “On the Great Wall”) set in Roman Britain, where the Romans are the imperialists and the British the ruled.

I like many of the short stories, especially the historical ones, and have reread Kim many times. But it is the poetry that really sticks. For other examples, illustrating the range of subjects covered:

“The Palace”—Kipling's verdict, I think, on his own career as writer: “After me cometh a builder/Tell him I too have known.”

“The Peace of Dives”—An allegory of economic interdependence as a force for peace. If I ever put together a collection of literature to teach economics, it will be included.

So I make a jest of Wonder, and a mock of Time and Space,

The roofless Seas an hostel, and the Earth a market-place,

Where the anxious traders know Each is surety for his foe,

And none may thrive without his fellow's grace.

“A Code of Morals” - The risks of inadequate encryption on an open channel.

“A General Summary”—Nothing much has changed in the past few tens of thousands of years:

Who shall doubt the secret hid

Under Cheops' pyramid

Was that the contractor did

Cheops out of several millions?

“Arithmetic on the Frontier”-The economics of colonial warfare:

The captives of our bow and spear

Are cheap, alas, as we are dear.

A point of perhaps renewed relevance today.

“Jobson's Amen” and “Buddha at Kamakura,” sympathetic portrayals of Asia set in contrast to English (and Christian) ignorant intolerance, show just how far Kipling was from the usual cartoon version of the British imperialist.

“Cold Iron” and “The Fairies Siege” are about the limits of physical force and so, I suppose, of political realism—while “Gallio's Song” is an approving description of how an empire deals with religious conflict.

“The Last Suttee” has one of my favorite examples of the use of meter in storytelling:

We drove the great gates home apace:

White hands were on the sill:

But ere the rush of the unseen feet

Had reached the turn to the open street,

The bars shot down, the guard-drum beat—

We held the dovecot still.

I'll stop now. For a pretty complete webbed selection, go to: http://www.poetryloverspage.com/poets/kipling/kipling.html

[This essay originally appeared as two separate entries on David Friedman's blog. It was revised and expanded for publication in Prometheus—editor]

|

All trademarks and copyrights property of their owners. |