Prometheus

Newsletter of the LFS

In searching for a term that describes bureaucratic senselessness and despair, a writer usually will reach for “kafkaesque.” This term is now so ingrained in the popular mind that the majority of people who understand this term have never read anything written by the Prague writer (1883-1924). Indeed, that term has bent back on the author himself, and imbued his works with meanings probably never conceived by this solitary and reclusive writer who came to fame mainly after his death. Had his friend and executor Max Brod not ignored 's request to burn all his papers, and instead edited these and published them as stories and novels, the world probably would have needed to find another term to describe that faceless aspect of the 20th century bureaucratic state.

Written in 1914-1915, but not published until 1925 as an incomplete novel, The Trial deals with Josef K., and his futile and confused struggle against an obscure legal system after he is arrested early one morning. The novel is a chaotic, despairing read, as K. struggles to come to terms with his strange arrest (he remains free to continue his work and also pursue legal recourses to his case, but in a court system like no other), and the bizarre people he encounters. There are many interpretations of the novel, but the one that has seized the imagination considers it a tale of bureaucracy gone mad, and a state that pursues legal proceedings with blind doggedness. Many writers and film-makers have echoed 's tale. One of these, Terry Gilliam's film Brazil, bears a stark resemblance to The Trial. In both cases it seems a misunderstanding is at play, with a smear on an arrest warrant sending the police after the wrong man in Brazil, and Josef K., a bank manager being confronted at his first hearing with the words, “You are a painter.”

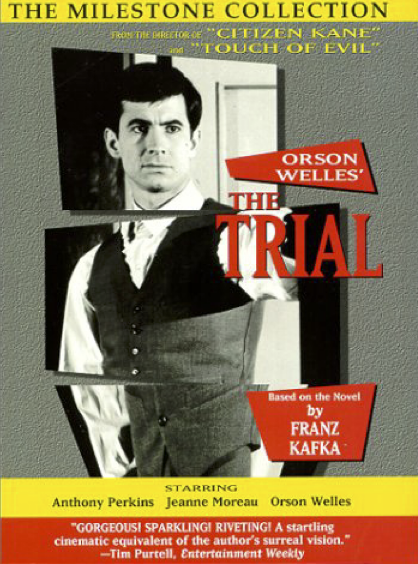

In 1962 the well-known director Orson Welles dramatized the novel in a black and white movie starring Anthony Perkins as Josef K., Welles himself as the Advocate, and a host of international actors in central roles. Filmed in Paris, Zagreb, Milan, and Rome, in an almost film noir expressionistic style, the movie hews closely to the novel, yet also creates its own version of 's story.

When I watched the movie my mind was clouded from having read the novel. When I read the novel, I brought a great deal of pop-culture baggage along for the ride. The essence of the book is fairly well-known, as these days it is nearly impossible to miss references to the book. A quick news search in Google produced nearly 150 hits on the term “kafkaesque” (including at least one commentary on the death of Alexander Solzhenitsyn); usually these stories are linked to trials or arrests under Byzantine and insane rules. I was surprised how this term is at best a superficial understanding of the novel, and really a misrepresentation in hindsight of for modern purposes. Often the term combines the sense of several stories, including The Judgment and The Castle, two equally despairing books. From a libertarian perspective, the state almost by immutable laws of nature becomes kafkaesque, and many 20th century instances of terror and injustice aptly can be termed kafkaesque, such as the Holocaust and the Soviet Union's Gulag system. The latter is a closer approximation of the senselessness of the state. In Nazi Germany the concentration camps and gas chamber largely was driven by an ideological hatred of Jews. In the Soviet Union any person could be classified as an enemy of the state, and once classified as such immediately arrested, tried, found guilty, and sentenced to hard labor in exile. While Josef K. is termed guilty from the start, and suffered the fate of many Holocaust and Gulag victims, his arrest is unique in that he remains somewhat free.

Several libertarian theorists (Etienne de la Boetie, Murray Rothbard, to name a couple) have written about the willingness of the victim to remain in his state. We surrender to the mystique of the state, and thus feel compelled to live by the rules of the state, working within the system for change, and seem surprised when the system twists and bends to remain unchangeable, instead breaking those to strive for radical change.

Josef K., portrayed by the lanky and almost boyish Anthony Perkins (fresh off his career-defining role as Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho two years earlier), bounces from place to place with seemingly no purpose. Although in reality some time passes from the moment K. wakes up to discover the police in his room to the moment he meets his fate, the movie never pauses. Each scene melds into the next, with Welles knitting together exteriors from different cities in the same scene, all contributing to a disconcerting sense of chaos and uncertainty. Perkins blusters and stammers, rages and stalks his way throughout the movie, never sure of the reason for his arrest or what recourse he has, and seemingly indifferent. Women throw themselves at him, from his landlady to his Advocate's nurse, as well as a charwoman in the court and a bevy of teenage Maenads. There are even two scenes with his not-quite sixteen year old cousin that hints at implied sexuality there. And yet, in most of K.'s encounters with these women he never pursues, but is always on the receiving end, always the one being seduced. Much like Hamlet's famed indecisiveness, K. embodies passivity. His one major act of defiance, one where he appears bound in his conviction, is when he dismisses his advocate, a man whom throughout the movie seems never to leave his room to advocate.

The Trial is one of those movies that you watch with an uncomfortable feeling, much like witnessing a person destroy themselves through drink, yet being unable to render any sort of aid, or even walk away. Although Welles called it “the best film I ever made,” it is not the sort of movie that will appear on a list of favorite movies. The entire movie is noted for its bleakness. Filmed in black and white, it seems far older than its 1962 date. The novel itself is almost timeless, with no hints as to when or where it took place. The movie instead has a strong American focus, with the police alternating between American depression area gangsters and hardened cops interrogating K., answering every one of his questions with another question, and confiscating his identity papers without a glance at them to verify his identity.

And yet, even though it may not be a likeable movie, or contain any sympathetic characters (for unlike many a wrongly accused person hauled before the apparatus of the state, Josef K. seems like a dunce, a person without any moral compass, neither innocent nor guilty, merely unable to grasp his situation or the events around him), The Trial is an important movie. Much like 1984 and Brazil, it creates a dystopian setting against which the protagonist must struggle. None of these movies are cheerful. This is not a we-shall-overcome type film. But the fact that there is some resistance, some defiance in their lives shows the hope within that struggle. The 20th century is perhaps the true Dark Ages, as millions of individuals were sent to prison or death, and few of them resisted. Few of them expected the treatment they received, the inhumanity of their captors or even fellow prisoners. There's the danger of reading too much into these works, of attaching political meaning into every image, every line of dialog. Yet I could not but transfer some of the despair felt in the movie to the events between the novel's conception and the movie's release.

Is The Trial about the numbing effects of bureaucracy, one man's impossible odds against the vast machinery of the state? Perhaps. There are strong hints that rather it deals with god, not the state. The parable of the man before the law has a sense of religious conversion about it. The idea of K.'s guilt even without knowing the charge points to the idea of original sin. Perhaps it is not a political story at all. Perhaps it is a novel about male/female relationships, given the way women behave toward K. But still, we have appropriated it as such, giving it meaning beyond or contrary to what might have imagined. To understand the essence of the term “kafkaesque” one should read the book or see the movie. The disturbing images in both will linger long in your soul.

|

All trademarks and copyrights property of their owners. |