Prometheus

Newsletter of the LFS

Freefall has been appearing as a Webcomic since March 30, 1998. Recently, mentioned it at his Web site. His praise of its serious science fictional content made it sound interesting, so I took a look—happily, the entire run is available online! What I found was an entertaining story that does have actual scientific substance and also has a surprisingly libertarian worldview.

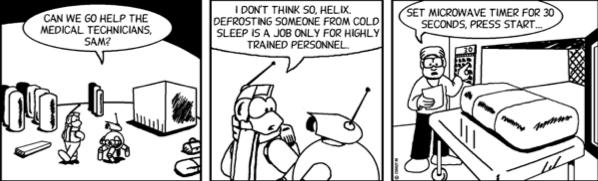

The premise sounds like the setup for a joke: “A robot, a squidlike alien, and a genetically enhanced wolf are the crew of a spacecraft.” And, in fact, much of the story is comedic, with some great dialogue and an often excellent sense of timing—for example, the pie-throwing sequence builds up to a perfectly timed climax. Nor is the comedy limited to “idiots, explosives, and falling anvils” (in the words of Bill Watterson); like much of the best comedy, it grows out of character.

In this case, though, the character is not only personal but species character: It reflects the distinctive origins of the various nonhumans. The robots are mostly programmed to follow 's Laws of Robotics, and Stanley's exploration of their logic is sometimes more ingenious than 's, not to mentioned often being funnier. The uplifted wolf, Florence Ambrose, has also had those laws programmed into her neural architecture—but overlaid on human-based cognitive architecture overlaid on the brain of a wolf, which gives her a lot of flexibility, enough to work around her constraints, increasingly easily as the story continues. This is helped by her exposure to the alien captain, Sam Starfall, a member of a race of land-dwelling cephalopods who attained intelligence as scavengers. In his native culture, theft, fraud, and trickery are considered virtues; he's not merely a cunning rogue, but a cunning rogue who in his own view is heroically doing what's right. A continuing motif of the strip is Sam and Florence each trying to set a good example for the other, taking pride in being a good influence, and worrying about being tempted—Florence into deceit and illegality, Sam into loyalty, truthfulness, and hard work!

In other words, this strip is in part about the clash of different moral perspectives. And that leads to one of its major continuing themes: The question of the rights of artificially created beings, such as robots and uplifted animals. It's established very early that Florence is not legally a person, but property: She belongs to the young human man whose family raised her, and whom she regards as her brother, though at this point in the story he's on his way to another solar system and has never appeared on stage. Moreover, the planet Jean, where the story takes place, is occupied by millions of robots, often highly sophisticated, who are regarded not as people, not even enslaved people, but as equipment. Both the robots and Florence are compelled to follow direct orders from human beings—and the category of “human being” is rigidly defined: neither Florence nor Sam counts as a human being. Both the robots and Florence are subject to reprogramming and memory erasure. This gives rise to one of the most brilliant scenes in the strip, in which Florence has been taken into custody by the corporation that manufactured her, and her recent memories have been erased but her sense of smell repeatedly enables her to reconstruct the events she has forgotten, and she begins leaving herself Post-it notes as an external memory. (Seeing this, I thought both of Echo in Dollhouse and of Qiwi Lin Lisolet in A Deepness in the Sky, two stories based in part on the horror of memory editing.)

This kind of story is naturally going to appeal to libertarians. But there are passages that suggest the author's sympathy for libertarian views. Early on, Florence asks the robot member of the crew, “Helix, how can you even think of breaking the law?” and gets the answer, “Sam's been teaching me. He says that blind obedience to the law could result in robots supporting a tyranny. We have to decide for ourselves if a law is just or oppressive.” And more than a decade later, this is exactly what happens in one of Freefall's major storylines.

There is also a lot of satire both of bureaucracy and of corrupt corporate management. And, even more strikingly, one fairly recent strip offers a comment on centralized corporate management of robot maintenance being inefficient, and letting robots keep some of their earnings to spend on their own maintenance producing optimized results, which could have come straight from Ludwig von Mises—as a throwaway line, but libertarianism needs more such throwaway lines in popular entertainment! Finally, this is a story that takes it for granted (though not all the characters do) that all rational beings need to be free and to have rights.

At a deeper level, this is a story about cooperation between very different people pursuing different goals, but finding ways to work together. And it's a story about the qualities needed for success in market competition: both the integrity, honesty, and hard work that Florence embodies, and Sam's ability to improvise and love of trickery. Seeing the two characters play off each other, more than anything else, makes Freefall a pleasure to read.

|

All trademarks and copyrights property of their owners. |